What is food allergy?

A food allergy is an adverse reaction related to food that’s mediated by the immune system. Once a person has a food allergy, they will have an allergic reaction every time they eat that food. Food allergy in general can be divided into three types:

- Immunoglobulin E (IgE) mediated (e.g. urticaria or signs and symptoms of anaphylaxis)

- Non-IgE mediated (e.g. Food Protein Induced Enterocolitis Syndrome)

- Mixed (both IgE and non-IgE) (e.g. Eosinophilic esophagitis)

Around the world, challenge-proven food allergy is around 8-10% among infants, but this reduces to 5% after 2 years of age due to food allergies such as cow milk and egg resolving early in life.

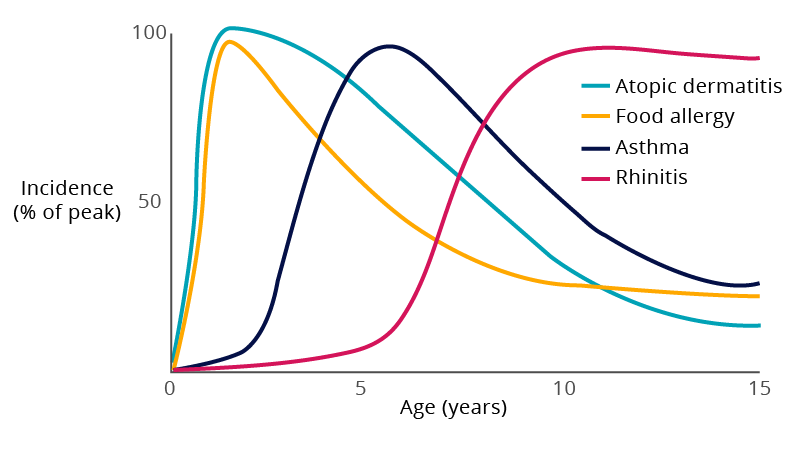

This early-infancy onset, shown in the chart below, contrasts with other atopic conditions, like asthma and rhinitis, which tend to present slightly later in childhood. This trend is referred to as the atopic march.

There are around 400 identified food allergens, but some foods provoke allergic reactions more frequently than others. Health Canada identifies these as the most common food allergens (bolded = most commonly found in children):

- Cow milk (and milk products)

- Egg

- Peanut

- Tree nuts

- Soy

- Seafood (fish, mollusks, crustaceans)

- Wheat

- Sesame

IgE-mediated food allergy symptoms usually develop within minutes of eating a food, but can occur up to 2 hours later.

The preference is to use age-specific language that parents can understand. Ask about these behaviours, which are indicators of potential allergic reaction that can be observed in non-verbal infants:

| Current Language (Category) | Infant/Toddler Specific Language (Symptom) |

| Pruritus | Tongue thrusting/pulling, lip licking/smacking, ear pulling, scratching or putting fingers in ears, eye rubbing |

| Dyspnea | Belly breathing, fast breathing, nasal flaring, chest or neck ‘tugging’ |

| Stridor | Hoarse voice or cry; barky ‘croup-like’ cough |

| Reduced blood pressure | Inconsolable crying, withdrawal, clingy, unusually pale, lethargic, limp, difficult to wake |

| GI symptoms | Vomitting, diarrhea |

Resource: Reducing Risk of Food Allergy in Your Baby

Why does the skin play such an important role in the development of allergic diseases?

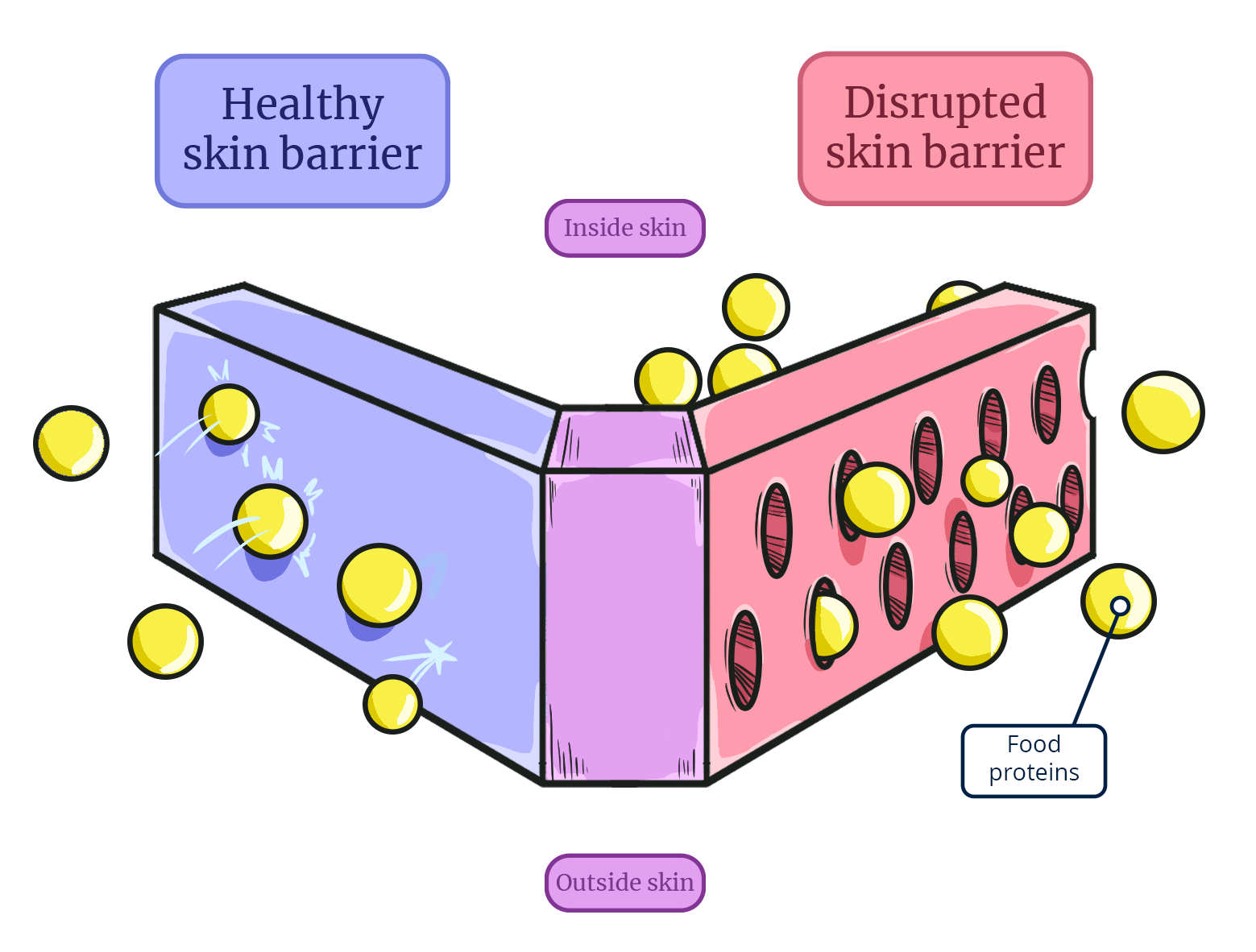

The skin is the largest organ of the immune system, and when it comes into contact with proteins, they are identified and tagged as either “self” or “non-self” by the immune system. Normally, these non-self proteins are blocked from crossing through the skin. With a healthy skin barrier, the immune cells beneath the skin never come into contact with food proteins. However, when the skin barrier is disrupted by skin conditions, such as atopic dermatitis or keratosis pilaris, the immune system can meet new proteins, such as food antigens, through the skin, rather than the gut.

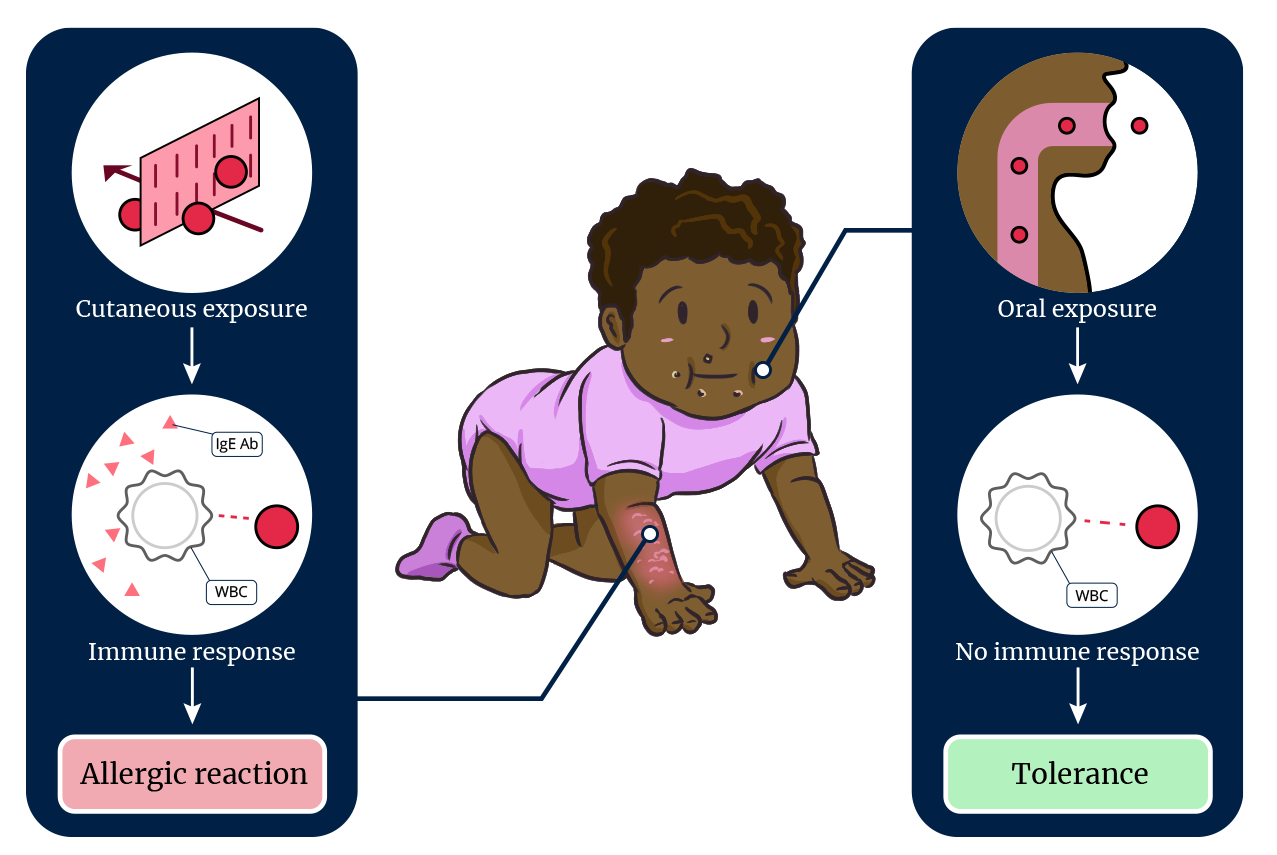

When an infant’s immune system is exposed to the food antigen through the gut via oral ingestion, the antigen is processed as a non-threat to the immune system and tolerance is more likely to develop. However, if the immune system’s first exposure to a food antigen is through a broken or damaged skin barrier, the immune system will consider that food as a foreign substance, triggering the body's white blood cells (WBCs) to begin producing allergy IgE antibodies (IgE Ab) against it. Upon subsequent ingestion of the food, the immune system is primed with these IgE-antibodies, and an allergic reaction ensues, often upon the first few exposures to the food.

Video demonstration of using an epipen on an infant

Source: Preventing Food Allergies in Infants: Early Introduction to Allergenic Solids